Niño Fidencio: A ghost in the family

The strange life - and afterlife - of a Mexican folk saint

October has always been my favorite month. The arrival of autumn, along with the general embrace of spookiness leading up to Halloween and Día de Los Muertos, brings back fond memories of childhood.

So, in the spirit of this season – with a horrifyingly consequential election weighing heavily on our minds – I've decided to do something a little different. I'm sharing a true but supernatural tale about a ghost that has had a major impact on my family, and on me.

So grab your mug of pumpkin spice and lower the lights. Throw another log on the fire if you've got one. Pile on an extra blanket or two. Settle in for a strange tale of mysteries and wonder from beyond the grave...

The Legend of Niño Fidencio

One year ago, I set out to write about a most unusual subject: Niño Fidencio. You’ve probably never heard that name, but Fidencio was once quite famous in Mexico. And though he died nearly 100 years ago, he had a dramatic and lasting effect on my family.

Let's start from the beginning:

In early 1928, insistent reports of supernatural events in a tiny desert village in northern Mexico captured the imagination of the Mexican public. Newspapers from Matamoros to Mexico City reported that a mysterious healer had begun performing miracles to cure the sick and dying. The people called him “Niño Fidencio.” He claimed to have received his curative powers after seeing a vision of the Virgin Mary in a pepper tree.

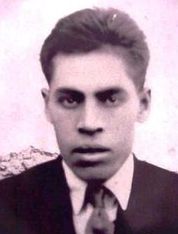

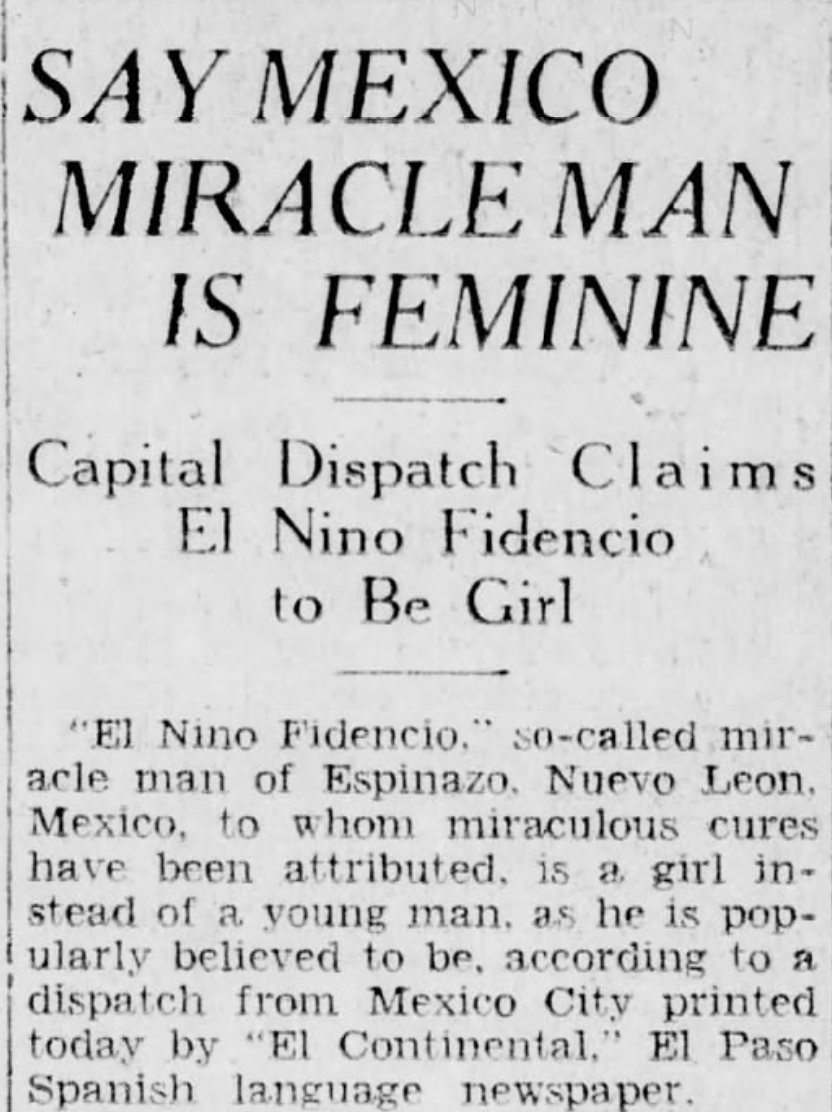

Fidencio – an illiterate kitchen servant with bare feet, a cleft palate and a gender we might today call non-binary – soon became the most famous person in the country. The press breathlessly covered his miraculous works. Tens of thousands of desperately ill Mexicans traveled to Espinazo, an obscure train whistle-stop in the Chihuahuan desert, to seek his aid.

Clad in a white tunic, the formerly unknown Fidencio bloomed into the role of holy man. He delivered sermons and performed cures as people crowded the village. His unorthodox healing methods included throwing fruit at sick people and using broken bottle shards to perform bloodless surgeries. He cured others by pushing them on a large swing or introducing them to his pet mountain lion, Concha.

“Public interest in both the rebel movement and General Obregon’s Presidential campaign has waned recently as the populace has devoted itself to extraordinary reports from Espinazo, a small village in the extreme north of the republic, where Niño Fidencio is reputed to be performing veritable miracles among the thousands of ill who have traveled there to consult him,” wrote the New York Times that year, during the peak of Fidencio’s fame. “Some believe him a genuine healer, but others declare him a charlatan.”

Fidencio’s mysterious rise came during a bloody conflict known as the Cristero War. It may seem hard to believe now that the Virgen of Guadalupe is the unofficial symbol of Mexico, but the Mexican government once tried to eradicate the Catholic Church. In 1917, the Mexican legislature, partly inspired by the Bolshevik Revolution, adopted a new constitution that toughened existing provisions to curtail the church’s influence. These laws went mostly unenforced until 1926, when President Plutarco Elias Calles launched an enthusiastic campaign of persecution against Catholicism. Tens of thousands of loyal Catholics took up arms against the government in response. The death toll reached an estimated 90,000 in three years.

In the midst of this brutal holy war, Fidencio rose up in defiance of both the government and the church alike. In a direct challenge to anticlerical laws that even forbade priests from wearing their robes in public, Fidencio launched a radical folk Catholic movement rooted in extreme public demonstrations of faith. Yet despite Fidencio’s professed loyalty to Catholicism, the church rejected his folk healing practices as heretical.

Such controversies helped spread Fidencio’s fame. With the surge in attention, his message turned increasingly messianic. He declared that Espinazo would become the “New Jerusalem” and welcome the second coming of Christ. His followers set up communal kitchens and hospitals to serve the masses. Tents and rickety shelters sprang up on the outskirts of the village to form a settlement that Fidencio called “El Campo De Dolor” – the “field of pain.”

"The poor are not poor, and the rich are not rich," declared Fidencio. "Only those who suffer from pain are poor."

Wealthy Americans began streaming into Espinazo as papers in the United States picked up the saga. President Calles, persecutor-in-chief of Mexico’s Catholics, eventually sought an audience with the desert mystic.

“President Calles, when traveling through Espinazo recently, visited Fidencio’s camp,” wrote the New York Times. “But reports that the president took a potion from Niño when banished his rheumatic pain instantly cannot be confirmed.”

By 1929, Calles had backed off of his crusade against the church, and Fidencio’s popularity had begun to wane. Demand for miracles had long exceeded his supply, causing corpses to pile up around Espinazo and fill the air with their stench. The press, which had done so much to build up the “miracle worker,” now proceeded to tear him down.

“A new cemetery for the ‘miracles’ of Fidencio,” snarked one headline.

Niño Fidencio dies – maybe

The crowds soon withered, leaving Fidencio with only a hardcore group of disciples. In 1938, he died under somewhat mysterious circumstances at the age of forty. Some of his followers insist that jealous doctors conspired to kill him. Others speculate that the healer died of poor health, long past his heyday and having sustained himself mostly on a diet of raw eggs and brandy.

Whatever the case, Fidencio's mourning followers would not allow his body to be taken from the room where he died. They buried him beneath the floor of his bedroom, and it became his tomb.

“Anyone who has read Emile Zola's description of those suffering human waves that came to Lourdes in search of relief from their ills, with their festering sores, their contracted limbs, their unspeakable diseases, but with a healthy and vigorous faith, the kind capable of moving mountains, will be able to form an idea of what Espinazo was like in those days,” wrote one obituary writer.

Niño Fidencio rises

What the obituary writers could not have guessed is that Fidencio would not remain dead for long.

Before he died, he promised his followers that he would continue to communicate with them from beyond the grave. Within days of his death, a cult movement sprang up to conduct ritual séances to “bring down the Niño” into the bodies of chosen spirit mediums. This folk cult spread throughout northern Mexico and followed migration routes north to Texas and California. Today, an estimated 100,000 people continue to revere Fidencio as a folk saint in Mexico and the U.S.

Strange? Yes. But this is not as unusual as it might seem. In the 21st century, belief in this kind of folk religion appears to be intensifying rather than shrinking in Latin America. Experts say more Latinos are embracing folk saints like Fidencio as the traditional church falls short of their needs.

From an Axios piece by Russell Contreras headlined "Alienated Latinos are turning to unofficial saints":

Devotion to unsanctioned Catholic folk saints is one of the fastest growing religious movements in Latin America and is surging in the U.S., experts say.

The big picture: Some Latinos who feel alienated by Christian traditions are turning to saints not sanctioned by the struggling Catholic Church for spiritual guidance around love, crime and money.

A family ghost

I know this trend from personal experience. You see, I spent part of my childhood in the cult of Fidencio. When I was young, my family regularly attended secretive ceremonies with dozens of other families. During these rituals, which took place in a converted garage amid the cotton fields of Tulare County, the “spirit” of Fidencio would speak to us for hours at a time through a local medium. Those communication sessions remain a vivid memory.

Here's how they worked: The adults donned white tunics, burned copal incense, and sang hymns to summon the spirit. The spirit medium stood at the front of an altar, deep in prayer. After several minutes of this, the spirit entered the body of the medium with tremendous force, making him gasp and choke for air. A couple of assistants rushed forth to clothe him in a white tunic, a wedge cap and a flowing satin cape.

By the time they had him dressed, and fitted with his large crucifix on a chain of pearls, he was speaking in the distinctively high-pitched voice of Fidencio. As Fidencio, the spirit medium ministered to the crowd, walking around the room with his eyes closed. He mixed herbal potions in a large glass bowl and splashed them over the heads of the congregants..

After giving a long sermon to the group as a whole, he gave private consultations to families, couples and individuals. One by one, families went up to see him at the altar – a tall, white wall of candles, photographs and vessels of water. They sought his consejos – his sage counsel on life, love, and the future. He offered his advice, performed cleansing rituals and even ordered people to lie on the floor as he stepped on their backs like a massage therapist.

As bizarre as this may seem to outsiders, this kind of everyday shamanism was quite normal in the pre-colonial Americas. It lives on today, providing an essential service in communities where access to mental health care is minimal or non-existent.

Health issues are what connected my family to Fidencio in the first place. One of my great aunts, seeking a cure for a sick relative, heard about him from a fellow farm worker. She became a devoted follower and recruited others in our family. By the time I was born, Fidencio loomed large in our lives. In some of my earliest memories, his dark eyes stare back at me from the black and white portrait on the family altar, or on the living room wall…

My parents divorced when I was six. After that, my link to Fidencio became increasingly sporadic. But the great mystery of his spirit never quite left my mind. What was that all about? Who was the strange man with dark eyes, the "saint" for whom my family had such reverence? Do ghosts really exist?

And then there was the prophecy. Before I was even born, Fidencio had predicted that I would one day become a "man of letters" and work with very powerful people and...

Boo!

I have never been religious and, believe me, such grandiose predictions seemed quite ridiculous when I was a high school dropout with long hair and a fondness for Metallica t-shirts. But my interest in Fidencio increased in college, after I read some anthropological works on shamanism. These got me interested in my own family ties to folk religion and the cultural practices that connect us to our indigenous ancestors.

A failed quest

In 2001, I set out to write the definitive tale of Niño Fidencio. I traveled to Espinazo, his home village in the state of Nuevo Leon, to attend the annual fiesta honoring him. I imagined myself to be writing a great “personal history” piece for the New Yorker. Being young, however, I got distracted into other adventures and failed to complete the project.

Soon afterward, I started working in politics as a spokesman for various California politicians. It became necessary to leave this fascinating tale of shamanism by the wayside ... for a while.

Last October – twenty years after my first journey, and having returned to journalism – I once again set out to write about Fidencio. I traveled to Mexico City and spent several days in the massive newspaper archive at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). I pored over the work of Dr. Tony Zavaleta, an anthropologist who has done more than anyone to illuminate the life of Fidencio.

Then I headed north to Espinazo, a few hours from the Texas border, to attend the annual fiesta held in Fidencio’s honor. (Imagine Burning Man, but for extremely fervent Mexican believers, some of whom crawl on their knees or roll their bodies along the dusty streets in brutal acts of penance.)

When I returned to the USA, I planned to block out the world and finally write my epic Fidencio piece. As I focused my mind on the dynamics of cult religion, however, I couldn’t help but notice some disturbing similarities to some other things happening in the world today.

How could I write about the tumultuous politics of Mexico in the 1920s with so many shocking things happening in today's news? How could I focus on a relatively small and harmless devotional movement when the emerging cults of Silicon Valley require such urgent attention? And so, once again, I found myself diverted from the story of Fidencio to the present moment ... and here we are.

Interestingly, 2024 is the year when I finally fulfilled my lifelong dream of being a magazine writer. My pieces on the Network State cult and the tech billionaires trying to seize control of our politics have gained a wider audience than I ever imagined when I started this newsletter as a way to keep track of my own observations. It wasn't a story I expected to tell, but it was a story I had to tell.

Yet it must be said that my important work on these matters is a direct result of my ongoing failure to write my epic Fidencio piece. By telling you this, I am holding myself accountable for that failure.

Things scarier than a ghost

Fidencio lived during turbulent and violent times. He catered mostly to the poor and the sick. Yet he reminded the powerful and the rich that they, too, will return to dust. He preached a gospel of faith and justice that gave people tremendous hope. He challenged authority and convention and expectations at a moment when it was very dangerous to do so.

Fidencio was full of contradictions. He was a humble peasant, but he loved to pose for the cameras. He attracted throngs of admirers from around the world, but he died sad and feeling like a failure. But then, of course, he didn't actually die. The impression he made was so profound that even now, nearly a century after his death, he lives on in the hearts and minds of those who revere him.

By studying history, one learns that things have never been easy. Every generation must fight and struggle to overcome the horrors of its times and further the cause of goodness and justice. Here in the 21st century, we confront serious threats on all sides. Greedy corporations conspire to destroy our planet. Evil authoritarians have risen up to seize power across the globe. Deranged billionaires, smelling opportunity in chaos, are making their moves to topple democracy and install themselves as the eternal winners of history.

It's all so much scarier than writing about a ghost! Here's to hoping that the 2024 election brings good news so I can finally return to this more pleasant assignment about the wondrous life – and afterlife – of Niño Fidencio.

Or else, it may be another 20 years or so...

Thanks for reading. More to come.

If you're interested in learning more, here's a short film Vice News did on Fidencio back in 2015: